In a cave on the coast of South Africa, paleoanthropologist Curtis Marean found the earliest evidence of humans eating shellfish: the 164,000-year-old remains of brown mussels and sea snails. Marean theorizes that when the Homo sapiens population dropped to just a few hundred due to the cold temperatures of Marine Isotope Stage 6, a glacial period also known as the late Illinoian glaciations, a small population survived by moving to the warmer coast and eating shellfish.

——

Approximately 80,000 years later, the first Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa. One theory is they followed the coast of the Indian Ocean to the Asian subcontinent. According to Smithsonian Magazine, “The migrants' path never veered far from the sea, departed from warm weather or failed to provide familiar food, such as shellfish and tropical fruit.”

——

Fifteen thousand years ago, their descendants followed mammoths across the Bering Land Bridge to North America.

——

“approach it as you will but do so knowing that the line which connects the perceptions to the perceived is crossed with the line of the needs and necessities and there at the crossing are the casualties fragments to stories some still struggling to find the beginnings” — Truong Tran, dust and conscience

——

Recent discoveries in Con Moong Cave in north central Vietnam suggest that humans have been living in Southeast Asia for more than 60,000 years.

——

The Poverty Point culture thrived along the Mississippi River from northern Louisiana to the Gulf Coast from about 1750 to 700 B.C. They traded with people from as far north as present-day Michigan and as far east as the Appalachians. They cooked in earth ovens, adding heated, hand-molded cooking stones. The shape and size of the stones controlled cooking times and temperatures.

——

On Tuesday, January 15, 1493, Christopher Columbus recorded in his journal, “There is also plenty of aji [chiles], which is their pepper, which is more valuable than pepper, and all the people eat nothing else, being very wholesome.” On that same day, he set sail from the shores of Hispaniola, landing in Lisbon on March 4, 1493.

——

In December 1497, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean in search of black pepper, cinnamon, and other spices. By 1528, there were three varieties of chilies growing in Goa, India.

——

“I saw you green, turning redder as you ripened ... Savior of the poor, enhancer of food, fiery when bitten.” — Purandara Dasa (1484–1565), of the first known mention of chiles in India

——

In Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes (1597), British surgeon and botanist John Gerad mistakenly describes the chile as originating in Africa and Asia: “The plants are brought from foreign countries, as Ginnie [Guinea], India, and those parts, into Spain, and Italy, from where we have received seed for our English gardens.”

——

In 2011, the top three chile producers were:

1. China, 15,520,000 tons

2. Mexico, 2,131,740 tons

3. Turkey, 1,975,269 tons

The Cook Islands were the smallest producer, growing a mere two tons.

——

“After they grow the pods, green at first, and when they are ripe, a brave color glittering like red coral, in which is contained little flat seeds of a light yellow color, of a hot biting taste like common pepper, as is also the pod itself, which is long and as big as a finger and sharp-pointed.” — John Gerad, Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes

——

The history of food is the history of humanity.

——

For at least 2,500 years before the arrival of the French in Louisiana in the late 1600s, the Chitimacha people lived in the Atchafalaya Basin, many around Bayou Teche, which they believed was created by the carcass of a giant snake killed by their ancestors.

In the Chitimacha creation myth, the Great Spirit, who was blind, created water, fish, and shellfish. Then it ordered the crawfish to dive under the water and dig up the mud that it would use to create the land.

The Indigenous People of southern Louisiana would catch crawfish with venison-baited reeds.

——

In the 1500s, Basque fishermen harvested cod off the Atlantic coast of present-day Canada. While trading with the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and other Indigenous People, a Basque pidgin developed.

——

Pierre Dugua de Monts and Samuel de Champlain left France in 1604 to establish Acadia, a French colony that occupied what are now the Maritime provinces of Canada.

Historical records imply that Mathieu de Costa joined de Monts and de Champlain around 1609. De Costa was an African translator who spoke Dutch, French, Portuguese, English, and Basque pidgin. He may have been the first African in North America.

——

In 1658, Ralph Leftwich migrated from Cheshire, England, to New Kent County, Virginia.

——

History isn’t narrative but the fragments of narrative.

——

In 1706, French in colonial Louisiana attacked a Chitimacha village killing everyone except 20 women and children. The French enslaved these survivors.

During a skirmish with the Spanish in 1710, the French captured a few enslaved Africans and brought them to Louisiana. They were first enslaved Africans in Louisiana. Between 1717 and 1721, the French shipped 2,000 enslaved Africans directly from Africa. Many were from Senegambia, a region between the Senegal and Gambia Rivers.

By the start of the Civil War in 1861, there were approximately 331,726 enslaved African Americans and 18,647 free people of color in Louisiana.

Many of Louisiana's enslaved African Americans were forced to work in harsh conditions cultivating and harvesting rice.

——

In 1727, Sister Marie-Madeleine Hachard, an Ursuline nun who migrated from Rouen, France, to New Orleans, wrote:

“We eat … peas, wild beans, several kinds of vegetables and fruits such as pineapple … watermelons, potatoes … figs, pecans, cashew nuts … wild beef, goats, geese, and wild turkeys, rabbits, chicks, ducks, pheasants, partridges, quail, and other fowl, and game of different kinds. The rivers are full of monstrous fish, especially catfish, which is an excellent fish … We accustom ourselves readily to the wild food of this land. We eat bread that is half rice and half flour ... What one eats more, and which is more common, is rice with milk and some sagamité, which one makes with Indian [corn] flour ground with a mortar. Then the flour is boiled in water with butter or some kind of grease.”

——

“In New Orleans and its environs, one does not lack for crawfish because there is such a great quantity.” — Marc-Antoine Caillot, a clerk in the French Company of the Indies who arrived in Louisiana in 1729

——

Joseph Broussard was born in 1702 in Port-Royal, the capital of Acadia. He traded with the Mi’kmaq and eventually learned their language. In 1710, the English conquered Acadia, but the Acadians never accepted British rule. In 1747, Broussard joined the Acadian resistance, eventually leading Acadians and Mi’kmaq in several raids against the English.

During Le Grand Dérangement (1755–1764), Broussard along with approximately 11,500 other Acadians were imprisoned or forcibly expelled from Acadia. Broussard was captured in 1762. After being released in 1764, he led a group of 200 Arcadian refugees to Louisiana, which was then a Spanish colony.

Louisiana was in need of more cattle. Since many of the Acadians were experienced farmers, many were granted upon arriving in Louisiana five head of cattle per family and land along Bayou Teche.

——

In 1766, Jean-Baptiste Semer, a 17-year-old who, after being separated from his family during Le Grand Dérangement, joined Broussard’s expedition to Louisiana, wrote:

“We already have oxen, cows, sheep, horses and the finest hunting in the world, deer, such fat turkey, bears and ducks and all kinds of game … The land here brings forth a good yield of everything anyone wants to sow. Wheat from France, corn and rice, sweet potatoes, Iroquois pumpkins, pistachios, all kinds of vegetables, flax, cotton … indigo, sugar, oranges, and peaches here grow like apples in France.”

——

“Fragments attract each other, a swarm of iron fillings … I keep going back to what we ate, what we were fed. It is my way of communicating with you, the other children in your houses.” — Bhanu Kapil, Schizophrene

——

In 1788, Pierre Pigneau de Behaine, a French priest, led one of France’s first forays into Vietnamese politics. While in the French Indian colony of Pondichéry (now the Indian union territory of Puducherry), he gathered a handful of French volunteers, a regiment of Indian troops, and two ships. With this force, he returned to Vietnam and unsuccessfully tried to place Nguyễn Ánh on the throne.

In 1887, the colony of French Indochina was established.

——

Though Afro-Creoles and African-Americans from Southwest Louisiana, what is often referred to as Cajun country, had been migrating to Houston throughout the early part of the 20th century, the destruction caused by the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 forced many more to move to the Bayou City. By 1930, approximately 12,000 Afro-Creoles and African-Americans from Louisiana were living in Houston.

——

In 1954 at Dien Bien Phu, the Vietnamese finally defeated the French and forced them from their country.

In 1965, the first U.S. combat troops were deployed to Vietnam.

In 1968, I was born in Chicago, Illinois.

During the late 1960s, my stepfather fought in the Vietnam War.

——

After the Fall of Saigon in 1975, South Vietnamese refugees began arriving in the United States. Many eventually moved to Houston and the Gulf Coast.

In 1975, approximately 500 Vietnamese Americans lived in the Houston area. By 2010, 34,838 Vietnamese Americans lived in the City of Houston and 110,492 lived in the Greater Houston area.

——

In April 2008, Trong Nguyen opened Crawfish & Noodles on Bellaire Boulevard in Houston’s Asiatown.

——

On Saturday, January 11, 2014, Chance and I ate at Crawfish & Noodles located at 11360 Bellaire Boulevard, Asiatown, Houston, Texas From the Cajun menu we ate:

Chicken Wings Nước Mắm

Spicy Turkey Neck in Broth

From the Vietnamese menu we ate:

Cua Rang Muối (fresh crab stir-fry with salt and pepper)

Mực Chiên Giòn (marinated squid stir-fry)

Crawfish Fried Rice

——

The history of food is the history of migration.

——

To eat with a three-pronged spear and a knife.

To eat with two wooden sticks.

To eat with the hands.

— Linh Dinh, “Earth Cafeteria”

****

A version of this timeline originally appeared in Sugar & Rice #2: Migrations

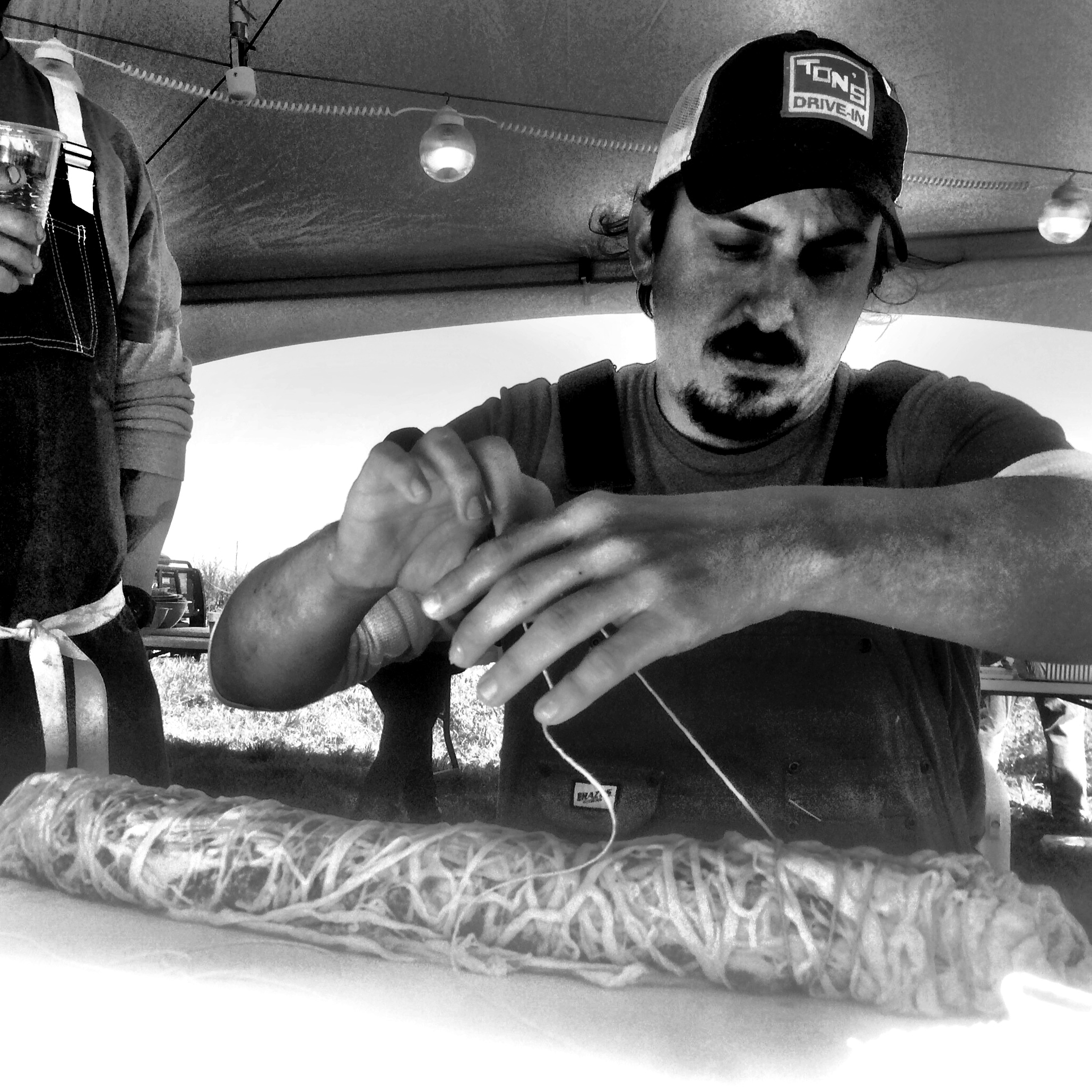

Photo by Chance Hunter